Barreras de acceso para la atención prenatal: experiencia en la Red de Salud Chiclayo, 2024

Resumen

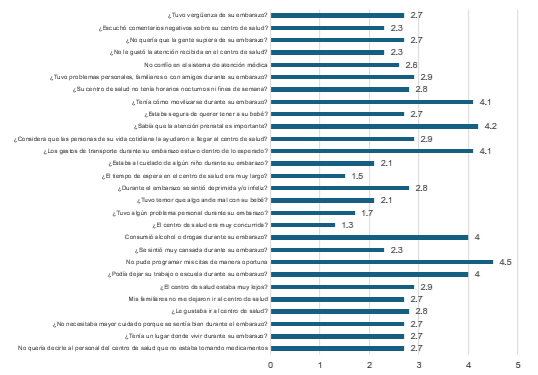

Objetivo: Determinar las barreras de acceso para la atención prenatal en la Red de Salud de Chiclayo durante el año 2024. Material y método: Estudio no experimental, de tipo correlacional y de corte transversal. Participaron 426 gestantes que recibieron atención prenatal en la Red de Salud de Chiclayo. Se empleó un muestreo no probabilístico por conveniencia y se aplicó el cuestionario Index of Barriers to Access to Care (ABCI), compuesto por 28 ítems en escala Likert de cinco puntos. Se analizaron medias, proporciones y correlaciones mediante la prueba de Spearman (Rho) utilizando el programa SPSS versión 22. Resultados: La principal barrera de acceso identificada fue la dificultad para programar citas oportunas para el control prenatal (94.1 %). También se reportaron limitaciones de transporte y gastos de traslado (69.5 %), así como dificultades para reconocer la importancia del control prenatal (78.8 %). Las diferencias por lugar de atención fueron estadísticamente significativas (p ≤ 0.005). A pesar de las dificultades mencionadas, el tiempo de espera para recibir atención no fue considerado prolongado por la mayoría de las gestantes. Conclusión: Las principales barreras de acceso identificadas se relacionan con la programación de citas, el transporte y los recursos económicos disponibles. Se recomienda fortalecer las estrategias de equidad en los servicios prenatales, mejorando la organización, el acceso geográfico y el apoyo financiero a las gestantes en situación de vulnerabilidad.

Citas

Holt V, Pelegrí E, Hardy M, Buchin L, Dapkins I, Chuang M. Patient-perceived barriers to early initiation of prenatal care at a large, urban federally qualified health center: a mixed-methods study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2024; 24(1): 436. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-024-06630-9

Yapundich M, Jeffries RS, Moore JB, Mayfield AM, Namak S. Evaluating Prenatal Care Compliance and Barriers to Prenatal Care Among Pregnant Individuals in Forsyth County, North Carolina. N C Med J. 2024; 85(6): 432–8. https://doi.org/10.18043/001c.121419

Cano Montesdeoca MV, Marrero Gonzáles D. Percepción de embarazadas sobre las barreras para el acceso al control prenatal. Revista Eugenio Espejo. 2024; 18(1): 39–57. https://doi.org/10.37135/ee.04.19.05

Reid CN, Fryer K, Cabral N, Marshall J. Health care system barriers and facilitators to early prenatal care among diverse women in Florida. Birth. 2021; 48(3): 416–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12551

Hoyos-Vertel LM, Muñoz de Rodriguez L. Barreras de acceso a controles prenatales en mujeres con morbilidad materna extrema en Antioquia, Colombia. Revista de Salud Pública. 2019; 21(1):17–21. https://doi.org/10.15446/rsap.V21n1.69642

Roozbeh N, Nahidi F, Hajiyan S. Barriers related to prenatal care utilization among women. Saudi Med J. 2016; 37(12): 1319–27. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2016.12.15505

Heaman M, Moffatt M, Elliott L, Sword W, Helewa ME, Morris H, et al. Barriers, motivators and facilitators related to prenatal care utilization among inner-city women in Winnipeg, Canada: a case–control study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2014; 14: 227. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-14-227

Cook CA, Selig KL, Wedge BJ, Gohn-Baube EA. Access barriers and the use of prenatal care by low-income, inner-city women. Soc Work. 1999; 44(2): 129–39. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/44.2.129

Hernández-Vásquez A, Vargas-Fernández R, Bendezu-Quispe G. Factores asociados a la calidad de la atención prenatal en Perú. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2019; 36(2): 178–87. https://doi.org/10.17843/rpmesp.2019.362.4482

McCauley H, Lowe K, Furtado N, Mangiaterra V, van den Broek N. What are the essential components of antenatal care? A systematic review of the literature and development of signal functions to guide monitoring and evaluation. BJOG. 2022; 129(6): 855–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.17029

Sandall J, Soltani H, Gates S, Shennan A, Devane D. Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016; 21(8): CD004667. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd004667.pub3

Rayment-Jones H, Dalrymple K, Harris J, Harden A, Parslow E, Georgi T, et al. Project20: Does continuity of care and community-based antenatal care improve maternal and neonatal birth outcomes for women with social risk factors? A prospective, observational study. PLoS One. 2021; 16(5): e0250947. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250947

Sutherland G, Yelland J, Brown S. Social inequalities in the organization of pregnancy care in a universally funded public health care system. Matern Child Health J. 2012; 16(2): 288–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-011-0752-6

Michel A, Fontenot H. Adequate Prenatal Care: An Integrative Review. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2023; 68(2): 233–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.13459

Sable MR, Stockbauer JW, Schramm WF, Land GH. Differentiating the barriers to adequate prenatal care in Missouri: 1987–1988. Public Health Rep. 1990; 105(6): 549–55. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1580177/

Rodriguez MI, Swartz JJ, Lawrence D, Caughey AB. Extending Delivery Coverage to Include Prenatal Care for Low-Income, Immigrant Women Is a Cost-Effective Strategy. Womens Health Issues. 2020; 30(4): 240–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2020.02.004

Nam JY, Oh SS, Park EC. The Association Between Adequate Prenatal Care and Severe Maternal Morbidity Among Teenage Pregnancies: A Population–Based Cohort Study. Front Public Health. 2022; 10: 782143. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.782143

Güneş ED, Yaman H, Çekyay B, Verter V. Matching patient and physician preferences in designing a primary care facility network. J Oper Res Soc. 2014; 65(4): 483–96. https://doi.org/10.1057/jors.2012.71

Wilburn SQ, Eijkemans G. Preventing needlestick injuries among healthcare workers: a WHO-ICN collaboration. Int J Occup Environ Health. 2004; 10(4): 451–6. https://doi.org/10.1179/oeh.2004.10.4.451

Aeenparast A, Tabibi SJ, Shahanaghi K, Aryanejhad MB. Reducing outpatient waiting time: a simulation modeling approach. Iranian Red Crescent Med J. 2013; 15(9): 865–9. https://doi.org/10.5812/ircmj.7908

Neutens T. Accessibility, equity and health care: review and research directions for transport geographers. J Transp Geogr. 2015; 43: 14–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2014.12.006

Roozbeh N. Explaining the preconception care utilization barriers, design, check of psychometric specifications, implementation tools and provide effective strategy [Tesis doctoral]. Teherán: Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences; 2016. p. 204–19.

McPake B, Witter S, Ensor T, Fustukian S, Newlands D, Martineau T, et al. Removing financial barriers to access reproductive, maternal and newborn health services: the challenges and policy implications for human resources for health. Hum Resour Health. 2013; 11: 46. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-11-46

Ogu R, Okonofua F, Hammed A, Okpokunu E, Mairiga A, Bako A, et al. Outcome of an intervention to improve the quality of private sector provision of postabortion care in northern Nigeria. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012; 118(S2): S121–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7292(12)60010-1

Penman SV, Beatson RM, Walker EH, Goldfeld S, Molloy CS. Barriers to accessing and receiving antenatal care: Findings from interviews with Australian women experiencing disadvantage. J Adv Nurs. 2023; 79(12): 4672–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15724